I've tasted a few black IPA's over the years and the ones I've liked the best are those that have absolutely no roasted barley flavor. These are rare, expecially here in Mexico. With a black IPA I want to close my eyes and taste a West coast style IPA with a boat load of hop flavor and aroma, subtle caramel and bread sweetness with a substantial bitter backbone. Then, I want to open my eyes and be shocked at the fact that the beer is jet black. This is my desire and what I attempt to do with the following session IPA recipe. I've complicated my efforts by using roasted malted barley. I could more easily use Sinamar but that product is too expensive and I think I can get the same results with a little extra effort.

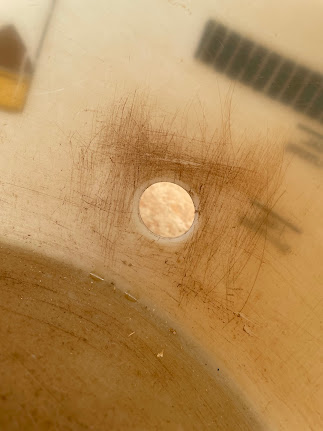

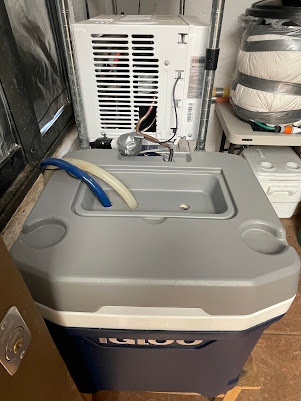

In this recipe I did a cold steep of 650 grams of Carafa III de-bittered barley in 2 liters of reverse osmosis water for 12 hours in the fridge. After this cold steep I ran the liquid through coffee filters trying to initially get as much of the wet grain dust out as possible. I then let this liquid rest for another 12 hours and decanted the liquid off the top of the remainder of the slurry that had settled to the bottom. On brew day, I heated the liquid to a simmer for 10 minutes to pasturize and finally, when I added it to the wort I found there to be some additional dust/slurry in the bottom of the pan which I was careful to leave out of the beer. Just pouring in the clearest of the Carafa liquid as possible.

Through this process I hoped to mimic Sinamar.

Here are the steps and ingredients for what I'm calling "BS IPA".

Black Session India Pale Ale